by Dr. Shane Steadman, DC, DACNB, DCBCN, CNS

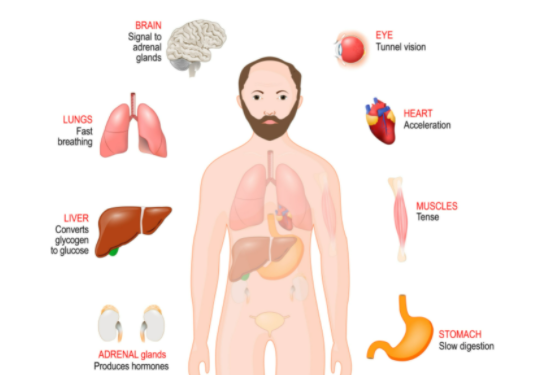

One of the oldest and most primitive areas of the brain controls our fight-or-flight response. Located in the midbrain, our fight-or-flight system automatically responds to acute stress, trauma, or perceived danger. This is a very necessary part of the brain when needed, but usually in small increments of time. We see examples of this when watching an intense or scary movie. We watch a character go into a dark alley downtown in the middle of the night. Suddenly, the person becomes aware of their surroundings, seeing shadows as the water droplets hit the pavement. Then a cat jumps out of nowhere, and they hear the proverbial pin drop. This type of suspense makes our fight or flight increase until we eventually jump out of our seats. This should be a temporary response where we feel our heart race, our breathing change, and our hands get clammy. We should be able to recover back to baseline quickly with no adverse effects.

Now imagine living in a state of fight or flight every day. This area of the brain easily turns on (triggers), yet their off button is broken. Another analogy, miles per hour hour (mph) describes the effect. Pretend a person’s fight or flight should be around 45 mph, a nice cruising speed easy to manage. When someone becomes stressed, their speedometer should go up to 75 mph and then back down. A person who experiences trauma and other types of PTSD might sit at 150 mph or even more. Their fight-or-flight system is primed and does not take much to stimulate it further. This is not sustainable for a long period of time without consequences. Like driving at high speed, the midbrain can seem out of control and difficult to manage. When people sustain a brain injury, trauma, or certain types of stress, the fight-or-flight area of the brain can stay elevated for days, weeks, or even years. This is like having the brakes go out with nothing to stop the fight-or-flight system. People who struggle with an overactive fight-or-flight system often have the following complaints:

- Light sensitivity

- Sound sensitivity

- Increased sensitivity to touch

- Heightened smell

- Changes in pupils

- Increased heart rate

- Shallow breathing

- Cold and clammy hands

- Racing thought

- Inability to stay asleep

- No tolerance for people in their personal bubble

- Tinnitus

One of the struggles with an increased fight-or-flight mechanism is the amygdala (limbic system) can also become elevated. The amygdala is responsible for fear and anxiety. Now imagine being fearful and anxious almost every day. Those struggling with an increase in fight or flight and the amygdala can become anxious about “trivial” things. What might be a small matter to others may be enormous to the person struggling with anxiety. Struggling with this can result in significant insomnia, OCD tendencies, phobias, and other anxiety disorders.

The big question becomes what can be done to help manage an increased midbrain, or what can be done when it speeds up and goes out of control. The first step is to identify the causes and triggers and reduce them as much as possible. Anything creating a stress response can result in a fight-or-flight response. This ranges from a food allergy to a stressful relationship. Counseling can be an important step in working on relationships, past traumas, and other causes of PTSD.

The next area to work on is the metabolic system. The metabolic system involves balancing hormones, stabilizing blood sugar, normalizing adrenal function, thyroid function, and even normal iron levels. A deficiency or an endocrine imbalance can impact brain function, creating internal stress or inflammation, which may cause an increase in fight or flight.

Finally, working with someone who understands functional neurology can be beneficial. An exam that looks at the different areas of the brain is important for developing a treatment plan to bring homeostasis. After a comprehensive workup, a treatment plan consists of dietary changes, supplemental support, metabolic support, neurotransmitter support, and brain-based therapies. Unfortunately, no one protocol fits all. Find a practitioner who understands the complexity of the fight-or-flight system to guide and advocate through the journey of healing.

Techniques that can be started now involve relaxation, breathing exercises, and medication programs. Many programs can be downloaded as an app. Equipment like blue-blocking glasses or rose-colored glasses, used when needed, can help calm the fight-or-flight response. People mostly wear these glasses with computer use, TV, or bright lights. Supplements that support GABA, adrenals, and inflammation can be a start to modulate the stress response and midbrain function.

The process may feel like trial and error, but each person differs with their own history and imbalances. The above is a good start, but finding a practitioner well-versed in this topic will be vital to the support system.

Dr. Shane Steadman, DC, DACNB, DCBCN, CNS, is the owner and clinic director of Integrated Brain Centers. To learn more about how they can help with concussions, stroke, and TBIs, please visit www.integratedbraincenters.com. For a free consultation, please call 303-781-5617.